- Home

- Kate Ristau

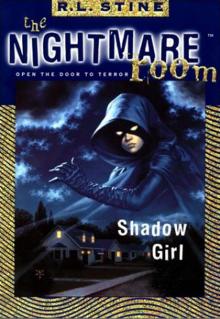

Shadow Girl Page 7

Shadow Girl Read online

Page 7

“Nothing,” Áine said, shaking her head in frustration. “It’s beautiful, but it doesn’t mean anything to me.”

“Do you think we’re in the wrong place?”

Áine clenched her teeth and kept looking. “Aunt Eri said it was here. I must not have seen it yet.” They walked up and down the narrow streets three more times until Áine finally groaned. “I don’t understand. It has to be here.”

“Maybe we should head back toward the docks? We could look—”

“Wait!” Áine said, her eyes narrowing on the horizon. She stared at a cluster of rowan trees off in the distance. “I remember those.” In her dreams, she had seen them. She had hidden behind them. They had held her up when she thought she would collapse.

She ran up the path toward them, and Hennessy followed close behind. Áine stopped beneath the canopy of leaves, staring up to the top of the ridge.

There, tangled in a web of ivy, sat the cottage where she was born.

A bed of flowers flanked the shiny yellow door, and children’s toys were strewn across the yard. Áine saw the window where she had stood, staring out into the rising darkness. Delicate lace curtains flanked the windowpane.

“No,” she whispered. “It can’t be—” Her voice broke, and she touched each trunk, feeling the bark underneath her fingers, cursing the memory, cursing the dreams. She stopped, staring at a pale grass ring in front of the cottage.

They tore her mother from the house, pulled her out the door, and carried her toward the pyre. She screamed and raged with such power that it shook the very darkness around them, but they dragged her forward, even as she scratched one of them in the face, leaving a long line of blood dripping down into his eyes. He cried out in pain, but they didn’t stop—they tied her to the post, running the rope along her arms and legs. She didn’t beg them to let her go, didn’t speak to them at all. As they lit the fire, as she started to burn, she just screamed, a pulsing, primal wail that tore through the night. It was inhuman. It was animal.

But they did nothing. Even him. Her father just watched her burn.

Áine fell to her knees, bursting into tears as the dream—the flames, the darkness, and the pyre—raged in front of her eyes.

Hennessy knelt down beside her and spoke quietly. “Áine...”

The rest of her words disappeared as Áine beat the ground with her fists, crying for them to stop, to let her go, to please—

“Áine,” Hennessy whispered. “It’s okay—”

“No,” she said “It’s not. Don’t you get it? Don’t you understand? It’s still there. The cottage. The window. The Oberon forsaken toys! Just look at them!” Áine threw her arm toward the cottage, toward the perfect little curtains and the tiny yellow flowers. She shook violently, and then her voice dropped. “I don’t understand. Why do people get to live here, and be happy here—why do they get to smile here, and laugh here, when she burned right here?” Áine rested her hand on the ground—the circle of grass where her mother had died.

“I don’t know, Áine,” Hennessy whispered. “I don’t know.” Hennessy pulled her into her arms, and Áine resisted, but then she collapsed into her.

“She burned right here,” Áine repeated. “They killed her. Why did they kill her?”

“I don’t know,” Hennessy repeated.

Áine clenched Hennessy’s shirt in her fingers and choked back a sob. It wasn’t enough to find this place. It wasn’t enough to come back home. She couldn’t stop them. She couldn’t put out the fire. Her mother was still dead.

Hennessy held her, rocking her back and forth, Áine’s head on her shoulder. Áine remained that way for a long time, her eyes wide open, staring into the past.

Eventually, Hennessy ran her fingers through her hair and lifted her chin. “We should go.”

Áine nodded, rising to her feet. She didn’t know why she had needed to see it, but now that she had, it changed nothing. She didn’t have some brilliant revelation that helped it all make sense. The past remained the same. If anything, it seemed darker.

She took one last look at the cottage, and then turned back to the path. “I want to find out what happened to my father.”

Nine

Áine kept a fast pace as they walked from house to house, knocking on doors in Baile An tSéipéil. But after the tenth house didn’t answer, her anger turned to frustration.

“Where is everyone?” she asked.

“It’s the middle of the day,” Hennessy said as she leaned against the side of a fence. “They’re probably at work.”

Áine could have sworn she saw the curtains move in the house behind Hennessy, but when she watched closely, she realized it was the wind blowing through the window. Nobody was home.

Áine clenched her fists, looking all around her for some sign of life. When she saw none, she finally gave in. “Let’s head down to the docks. We can find that old man.”

“Yeah. Maybe they have some type of historical society.”

Áine didn’t know what that meant, and she didn’t ask. She was already heading back down the road. If that man didn’t give her answers, she’d make him talk this time. He would tell her what she needed to know.

She tried to focus on what she would do, tried to focus on what was in front of her, tried to stay in the here and now. Most of all, she tried not to remember her mother. To see her—

Pushing the thought from her mind, she walked even faster. The salty wind whipped at her face, and she breathed it in, just wanting to be back to the water and away from that terrible place.

She had been walking for a while when she realized Hennessy wasn’t with her. She turned around and saw Hennessy sitting down in front of a wall, adjusting her boot again.

“Come on!” Áine yelled to her.

“I’m coming, I’m coming! Give me a break. Have you even seen my boots? Seriously, they’re great, but let’s be realistic, they’re not made for walking all over the Aran Islands.”

Áine walked back to where she was sitting and stared down at Hennessy’s black boots. They had pointy toes and a sharp heel. “What’s the point of wearing something you can’t walk in?”

“Says the girl from the Aetherlands who doesn’t even wear shoes. Aren’t your feet freezing?”

Áine looked down at her feet. “No. They’re fine. They don’t hurt at all. I don’t even get why you’re wearing those.”

“It’s called ‘fashion,’ my dear. And even if I can’t kick it as hard as you can on the hills, I look damn sexy.” Hennessy smiled and patted the ground beside her. “Now, sit.”

“But—”

“No buts. I am freaking starving over here.”

“Sorry...I didn’t mean to...I want to stop, but with those men, and Creed, I just don’t think it would be a good idea. Can we get back to town first? I don’t like being out in the open like this.”

Hennessy looked around, then shrugged her shoulders. “At least Creed can’t get a ferry across today. We got that on our side.”

“Yeah, but he can easily get his own boat. And he probably did by now.”

“Thanks, Debbie Downer. I was just starting to think a little positive.”

“You’re welcome. So, you get what I mean?”

For some reason, Hennessy smirked. “Yeah.”

“Good. Let’s go talk to that old man and see—”

“Stop talking, and let’s do this.” Hennessy pulled off her boots, stood up, and shoved them under her arm. Then she took off, running down the hill.

“Hey!” Áine yelled. “Wait for me!”

“No way! I’m not waiting around for you and your psycho-guys!”

Áine laughed as she ran down after her. The air slipping in and out of her lungs and the feel of her feet hitting the ground calmed her, tamped down the fear.

She loved to run. Loved the way it made her feel. The night after her last big fight with Aunt Eri, all she had wanted to do was escape, to break into a run and leave everything else behind her. She h

ad knocked on Ciaran’s window, dragged him out of bed, and raced him to the riverbank, the cool morning air biting at her cheeks.

By the time she got to the river, she was starving. She collapsed beneath the Singing Tree and waited for Ciaran. Her legs were pulsing, but her breathing was easy.

Ciaran fell down next to her several minutes later. “You cheat?” he asked in between ragged breaths.

“Never,” Áine replied.

“Didn’t even ask Tiddy Mun for some help?”

“Nope,” she replied.

“I did,” Ciaran said. “And you still beat me. I thought you were supposed to be the Shadow. All weak and stuff.”

Some of the joy of the run faded with his words. Because that was the problem: she was a Shadow. She looked over at Ciaran’s perfectly sculpted face, his blond hair and golden arms. He was attractive—she knew that. And he was her closest friend. But he was still so different than her. She stared down at her long legs.

“I’m leaving tomorrow,” she said.

He didn’t take that well. They argued until they were both exhausted, and the hunger had turned to a dull pain. She didn’t know what else to say to him.

The next day, Ciaran begged again to go with her, but she crossed the Threshold alone.

And now she was running in the Shadowlands, thinking about how she had left him there. No wonder she drove him crazy. He just wanted something simple. Easy. And she didn’t know what she wanted.

Áine glanced over at Hennessy. Sweat dripped down her forehead, and several locks of her jet-black hair were sticking to the side of her face. Hennessy caught her eye and then ran even faster.

She was so different from Ciaran. They were both smart and attractive, but Hennessy seemed so much more alive. Like the fires that lit up the sky on Midsummer Night. Warm and inviting, but also wild and unpredictable.

Her stomach broke through her daydreaming, growling in protest. She caught back up to Hennessy. “You wanna take a break?” she asked.

“Hells yeah,” Hennessy said. “My side is killing me.”

Áine gestured toward a tall ash tree on the other side of a rock wall. They climbed over the low wall, and Hennessy collapsed beneath the tree while Áine unloaded the food. Four pieces of bread, and three tins of food. Áine tossed two pieces of bread to Hennessy and then shoved some in her own mouth.

“You realize we are probably running straight toward him?” Hennessy mumbled between bites.

“Creed?” Áine shoved the last of her bread into her mouth and opened one of the tins of food. It looked like potatoes. “I know.” She wished he was dead. Or bored of chasing them. Or bored and dead. “Can I just act like it’s not a really stupid decision?”

“As long as you’re ready for him,” Hennessy said. “And as long as there’s less running, and more food.”

With a flourish, Áine passed Hennessy the tin of potatoes and a spoon. “As you wish.”

“Colcannon!” She shoved the spoon in her mouth and then went back for more. “This is deadly,” she said, going in for another bite. “That old langer was right. His wife makes a wicked colcannon.”

Áine grabbed the tin from Hennessy and took a bite. The taste was heavenly. Soft and buttery but also chewy and creamy.

“Come on! Leave some for me!”

Áine passed the tin back to Hennessy and opened up the other one. That tin was full of a strange dark mound, covered in some type of sauce. It reminded her of something...what was it? Some unpleasant memory lingered in her mind. She covered her mouth and passed it over to Hennessy.

“Not a fan of beef? That’s okay. I’ll eat it. I’ll eat anything. I’m like a human garbage disposal. You can have the applesauce.”

As Hennessy passed her the tin, Áine caught a flash of movement on the path. She touched Hennessy’s leg and gestured down the hill. They both ducked down and peered out from behind the tree.

Hennessy stifled a laugh, and Áine shushed her.

“Seriously,” Hennessy whispered. “You are so charmed. What are the odds?”

“I don’t know, but I’ll take them.” Áine turned back and pulled Hennessy close. “Let me do all the talking this time.”

“That’s a good idea. Work some of your magic, eh?”

“Not right away. I just don’t want you to scare him off.”

Hennessy elbowed her in the ribs.

Áine smirked and rose to her feet. “Good day,” she said.

The old man stopped cold, and then slowly shook his head. “I don’t want no trouble from you. I closed up shop for the day. I’m headed home. You should do the same.”

Áine took a step closer to the man and he took a step back. “I don’t mean to scare you. And I don’t want anything from you. I just want to know what happened.”

“I ain’t got nothing to say. Good day.” He turned and began walking quickly back the way he came. Áine jumped over the wall, and ran until she caught up to him.

“I know you know something,” she said. “You need to tell me. What happened to them? What happened to my mother?”

The blood drained out of the old man’s face. “I can’t—”

He wavered on his feet. Áine caught his arm, righted him, and stared into his eyes. “You were there, weren’t you?”

“It’s true, then,” he said. “You’re alive. And you’re so young.” His fingers dug into Áine’s arm. “He always said you were. Said he heard stories. Told me about them. But then that man came around and started asking questions. And people started disappearing. That’s when I closed my mouth. I ain’t heard or said a word about nothing since.”

“Let me guess,” Áine said. “Black tattoos? Big scar on his face?”

The old man nodded.

Áine sighed. “His name’s Creed. Listen, we’ve already dealt with him. You don’t have to worry about him anymore. Please—I just want to find out what happened.”

“Why don’t you leave me alone? Why don’t you just go ask him?”

“Creed?”

“No. Your father.”

Ten

“Wait—what? He’s alive?”

“Yes.”

“How...” Áine couldn’t process what he was saying. Couldn’t understand how it was even possible.

“It doesn’t make sense to any of us either, but he is. I was just a little boy when it happened. Shouldn’t have even been there. Your father, he’s over one hundred and eight years old now. He was a young man when it happened—”

Áine could taste the bile in the back of her throat as she let go of her hold on the old man. “Don’t call him that.”

“What?”

“Father. He’s not my father. He lost that the day he watched her die.”

The old man swallowed hard, and continued with his hands shaking: “Áine, there’s more to it than that. He spent years searching for you. Decades. He never gave up hope.”

“But he gave up on her when that bonfire lit up the night. Sure, he fell to his knees in regret when it was done, but he didn’t stop them. He stood by and watched her burn.”

“We all did.”

“Why?” Áine grabbed his shoulders and shook him. “Why did you just stand there? What happened?”

“Please—don’t make me tell that story. It’s not mine. I don’t want it. I never wanted it. It’s been burned in my mind since I was a little boy. Don’t make it burn any brighter.” The old man crumpled into her arms, but she refused to hold him up. She pulled him to his feet and loosened her fingers from his shoulders.

“Where is he?”

“Not far. Just up by An Tra. But please—he’s not right. There’s something dark about him. It’s like the night never leaves him. And he’s stretched so thin.”

Áine thought about how the years must have ravaged him. Somehow he had held on. So little time had passed in the Aetherlands, but so many years in the Shadows. How was he still alive?

Was it luck that saved him? Was it faith? Or something else?

Áine couldn’t hold a thought in her head. Her mind skipped back through the years, trying to recall his face. His touch. Something more than that final memory. But all that came back was that pyre. That night. That choice.

“You look just like her, you know,” the old man said. “Nia. Her face—I’ll never forget her face.”

“Neither will I,” Áine said.

She turned around and walked back up the road. She offered the man no solace—no redemption. He’d have to find that along another path.

* * *

Hennessy and Áine walked down the road in silence until Hennessy finally asked, “Why didn’t you make him tell you the whole story? You could have, you know. Why do you always have to be so nice?”

Áine laughed darkly. “Nice?” she asked. “Nice? You think it’s niceness that held me back? That I felt bad for the old man? Not even a little bit. He doesn’t deserve that release—that freedom—that comes from telling me what happened. He’s lived with it for ninety years—he can live with it till he dies.” Áine could feel the rage filling her chest, her breath speeding up. “He’s just like him. My ‘father.’ He stood by and watched her die.”

“He was just a kid, Áine.”

“Does that make it right? Does that make it okay? We’re just kids, Áine. What would you have done?”

Hennessy stared at Áine for a long moment, and then finally replied, “It’s not the same thing, and you know it. You need to stop blaming everyone—”

“I don’t need to do anything, Hennessy. It’s my choice. And maybe I don’t want to forgive them.”

Hennessy sighed and turned away. “I didn’t say you should forgive him,” she said over her shoulder. “But you can’t live like that, girl. With that much weight. That much anger. It’ll crush you.”

Áine tried to think of a snippy remark, but nothing came. She followed slowly behind Hennessy, dragging her feet along the dusty path, wanting to kick something. Or hurt someone. She didn’t want to let it go. And she wouldn’t. Her mother hadn’t had a choice or a chance. She would see it through for her.

Shadow Girl

Shadow Girl Shadow Queene

Shadow Queene